The Lead Up

On the morning of April 30th, 1789, New York City was abuzz with activity. The ceremonies began promptly at sunrise with artillery charges from Old Fort George, near Bowling Green.

At 9 AM, the bells of churches began to ring and continued for about half an hour, calling their congregations to their respective places of worship. Meanwhile, the military began to set up and make preparations for the parade. At the close of services and just as the people were leaving the churches, the procession began to form.

The military marched from their respective quarters with inspiring music and unfurled banners. A part of the procession came direct from Federal Hall. Following Captain Stakes with his troop of horse were the “assistants”: General Samuel Blatchley Webb, Colonel William S. Smith, Lieutenant-Colonel Nicholas Fish, Lieutenant-Colonel Franks, Major Leonard Bleecker, and Mr. John R. Livingston. Following the ” assistants were Egbert Benson, Fisher Ames, and Daniel Carroll, the committee of the House of Representatives; Richard Henry Lee, Ralph Izard, and Tristram Dalton, the committee of the Senate; John Jay, General Henry Knox, Samuel Osgood, Arthur Lee, Walter Livingston, the heads of the three great departments; and gentlemen in carriages and citizens on foot.

This group entered Franklin Square, where at twelve o’clock they paraded before Washington who stood before the Presidential mansion. The house was a large, 3-story brick building with a flat roof located on Cherry Street. It was owned by Samuel Osgood, of the Treasury Board, who moved out to give room for Washington and his family while in New York.

The Procession

The full procession, which amounted to about five hundred men, left the presidential mansion at half-past twelve o’clock and proceeded to the Federal State House via Queen (now Pearl), Great Dock, and Broad Streets. Colonel Morgan Lewis, acting as grand marshal, and attended by Majors Van Home and Jacob Morton as aides-de-camp, led the way.

Then followed the troop of horse, the artillery, the two companies of grenadiers, a company of light infantry, and the battalion men led by Major Bicker and Major Chrystie; a company in the full uniform of Scotch Highlanders, with the national music of the bagpipe the sheriff, Robert Boyd, on horseback, and the Senate committee; the President in a state coach, drawn by four horses, and attended by assistants and civil officers; Colonel Humphreys and Tobias Lear, in the Washington’s own carriage; the committee of the House; also Mr. Jay, General Knox, Chancellor Livingston; his Excellency the French Minister, Comte de Moustier; and his Excellency the Spanish Charge d’ Affaires, Don Diego Gardoqui; other gentlemen of distinction, and a large group of citizens.

The two companies of grenadiers attracted much attention. One, led by Captain Harsin, and composed of the tallest young men in the city, were dressed in blue with red facings and gold-laced ornaments, cocked hats, with white feathers, with waistcoats and breeches and white gaiters or spatterdashes, close buttoned from the shoe to the knee and covering the shoe buckle. The second, a German company, under command of Captain Scriba, wore blue coats with yellow waistcoats and breeches, black gaiters, similar to those already described, and towering caps, cone-shaped, and faced with black bear-skin.

The parade arrived at Federal Hall at one o’clock. The building had been crowded since ten o’clock and when the Senate met at half-past eleven the crowd started to grow excited. The military proceeded and when within two hundred yards of Federal Hall they formed up two lines on either side of the street. Washington with his assistants and the gentlemen especially invited, passed through the lines with hats in hand—the troops presenting arms and lowering the flags to the President. The group proceeded to the Senate chamber of the Federal State-House in a ceremonious manner.

The Inauguration

As Washington entered the Senate chamber, the Vice-President, and all the members rose to receive him. Washington was preceded by their chairman and introduced as they advanced between the Senators and Representatives, bowing to each. He was then conducted by John Adams, standing in front of his chair, which was placed to the right of the President’s seat.

The Senators were arranged in one of two rows of chairs on the right of Washington and next to the Vice-President’s chair; the other row being occupied by the late President of Congress, the Ministers of State, War, and Exchequer, the Ministers of France and Spain, the chaplains of Congress, the escort of the President, the Governor and Lieutenant-Governor of the State, the Chancellor, Chief-Justice and other judges of the Supreme Court, and the Mayor. The Speaker of the House of Representatives sat in another chair on Washington’s left side, and the Representatives sat in rows on that same side.

After everyone had taken his seat, Vice-President Adams said, “Sir, the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States are ready to attend you to take the oath required by the Constitution, which will be administered by the chancellor of the state of New York.” I am ready to proceed,” was Washington’s reply.

A balcony adjoined the Senate chamber, which permitted the crowd below to witness the ceremony. Three doors connecting with this balcony were opened. All those present arose, the Vice-President then conducted Washington to the balcony and followed by the Chancellor of the State, and other gentlemen accompanying in the order prescribed. The balcony itself overlooked Broad Street and had a canopy on it, from which hung curtains of red inter-layered with white.

The scene down Broad and Wall streets, in each direction, was a compact mass of crowds. The spectators had even gathered on rooftops, just to get a glimpse of the proceedings. Washington cut a commanding form as for the occasion he was dressed in a dark brown suit, of American manufacture (made in Hartford, Connecticut) and trimmed with “Eagle” metal buttons. He also wore white silk stockings and shoe-buckles of plain silver. His head uncovered, with his white powdered hair gathered and tied in the fashion of the day. To his side, he carried a steel-hilted dress sword. In this manner, he stepped atop a stone elevating him above the assembly of men on the balcony.

Robert R. Livingston, the Chancellor of the State of New York and Grand Master of Masons in New York State moved to the balcony. Jacob Morton, the Marshall for the parade and the Master of St. John’s Lodge, provided the Bible of the Lodge for the inauguration ceremony.

Besides these gentlemen who stood near Washington, on the balcony of Federal Hall, during the inauguration ceremony, were Secretary John Jay, Roger Sherman, Richard Henry Lee, Alexander Hamilton, Generals Henry Knox and Arthur St. Clair, Baron Steuben, and Samuel A. Otis, the Secretary of the Senate, Ale and in the rear Senators and Representatives and other distinguished officials.

The Bible that used was published in London by Mark Baskett in 1767, and was already of some age at this point. Owned by St. John’s Lodge of New York and used as the Lodge’s regular Bible, it was rather large and more illustrative than most bibles in that day. With two deep red leather covers, it was carried out on a rich crimson cushion. It was then opened and Washington placed his right hand on Genesis, Chapters 49 and 50. A copper-plate engraving explaining the forty-ninth chapter of genesis is one page, the opposite page having a leaf of turned down – which was the very page that Washington kissed. To find out more about the history of the St. John’s Lodge Bible, click here.

Before the assembled crowd of spectators, Robert Livingston, clothed in a full suit of black cloth and wearing the robe of his office, administered the oath of office prescribed by the Constitution: “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” After repeating this oath, Washington kissed the Bible, adding with eyes closed, “so help me God.”

“It is done” decried Chancellor Livingston. He turned to the crowd and loudly proclaimed “Long live George Washington, President of the United States.”

A flag was instantly raised upon the steeple of Federal Hall, and the bells in the city began to ring. Cheers and huzzahs burst forth from the waiting crowds and continued for some time. The city let fired off a 13-gun salute which was answered by 15 guns from the Galveston (ship-of-war of his Catholic Majesty) and in imitation other merchant vessels which were in the harbor followed suit. Cannon fire continued to be heard from multiple locations in the city – upon both land and upon the water, saluting the newly inaugurated President.

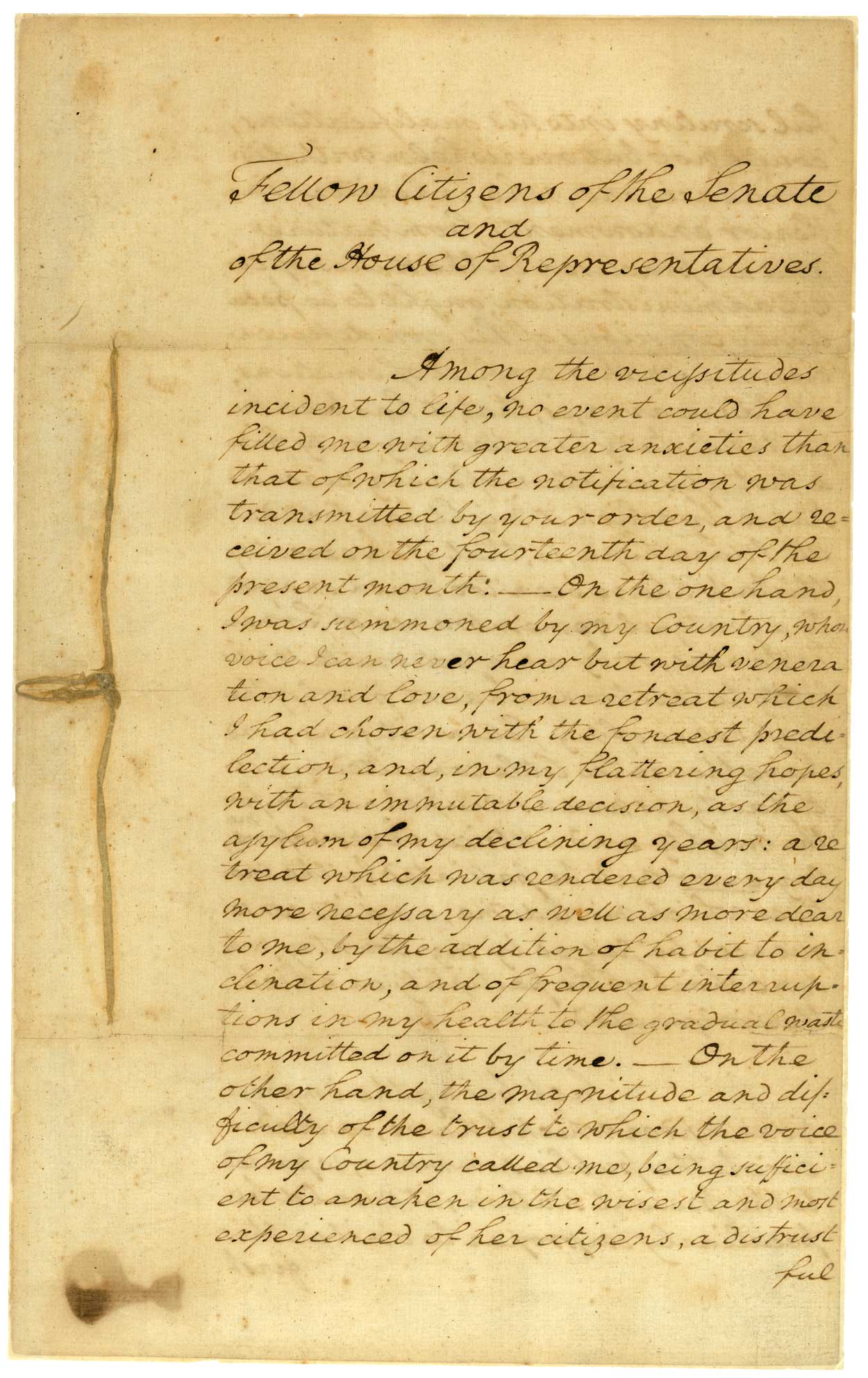

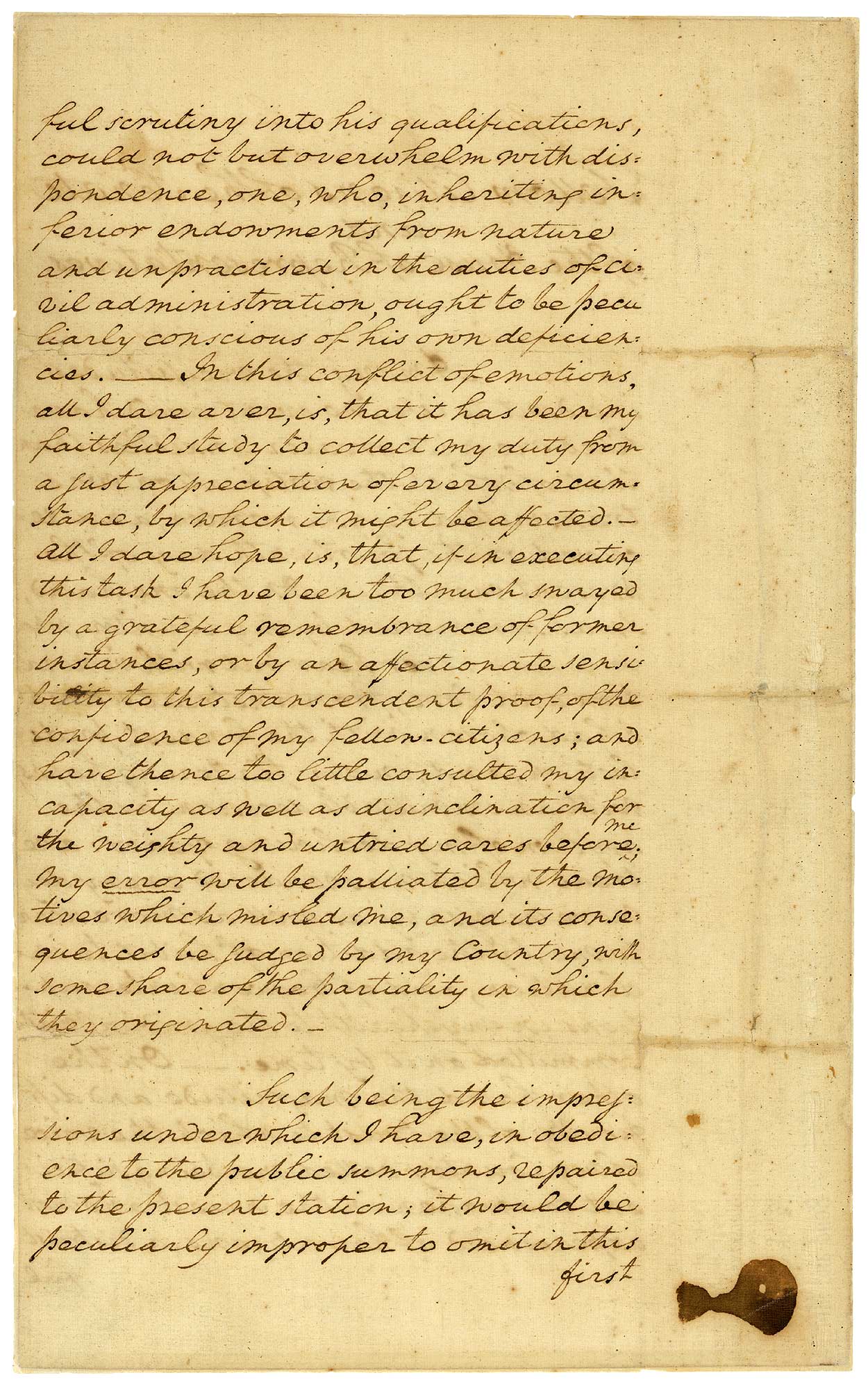

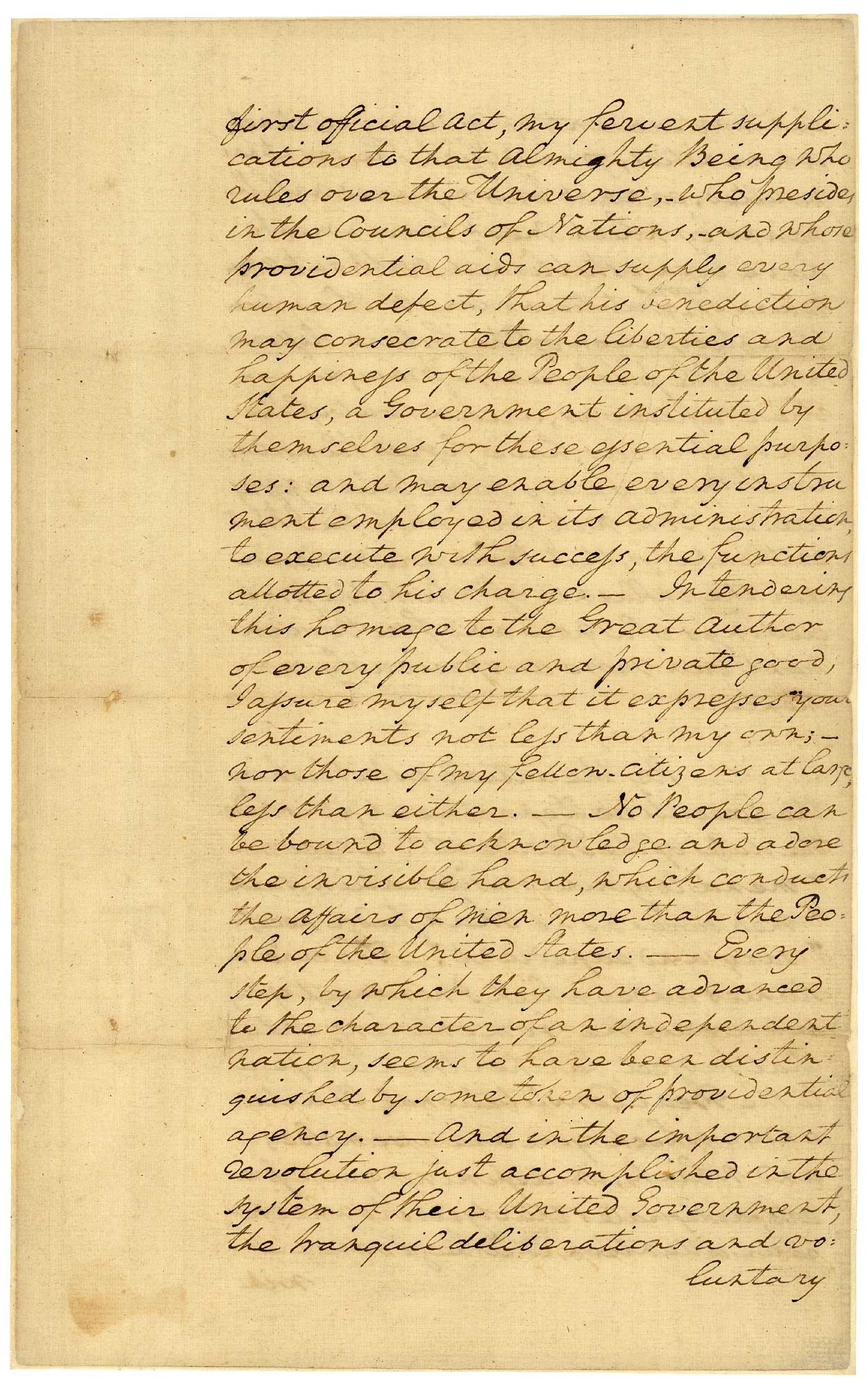

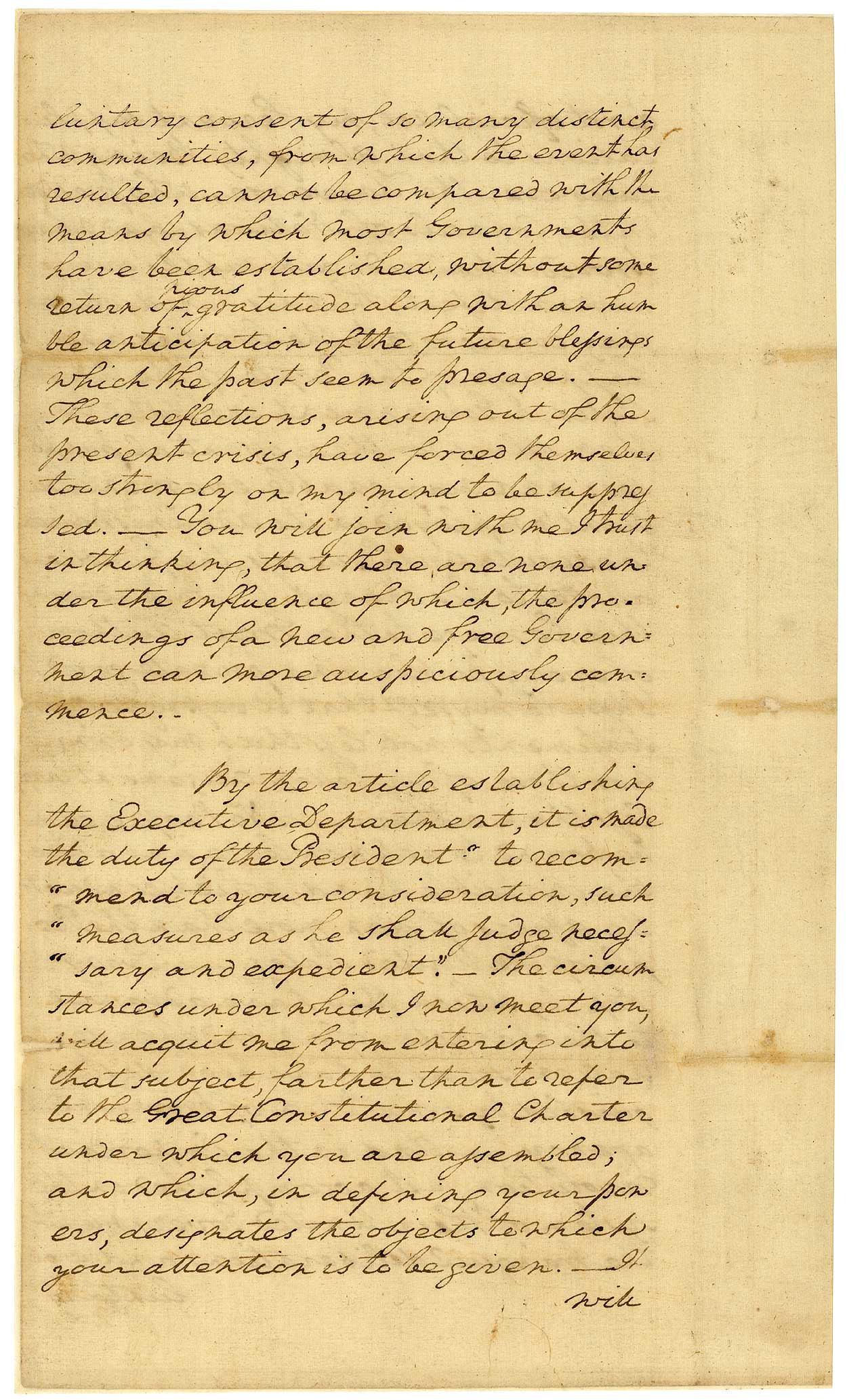

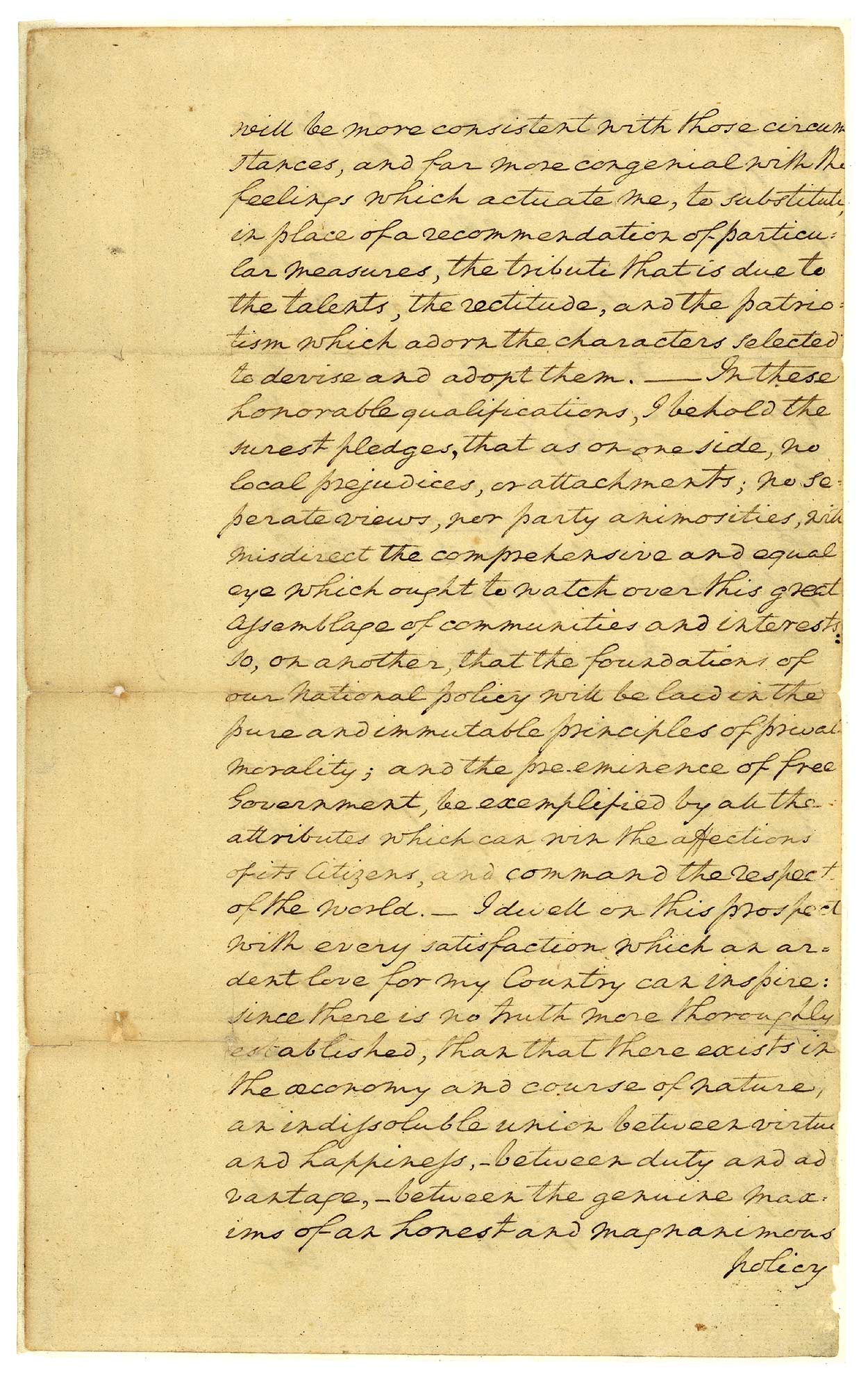

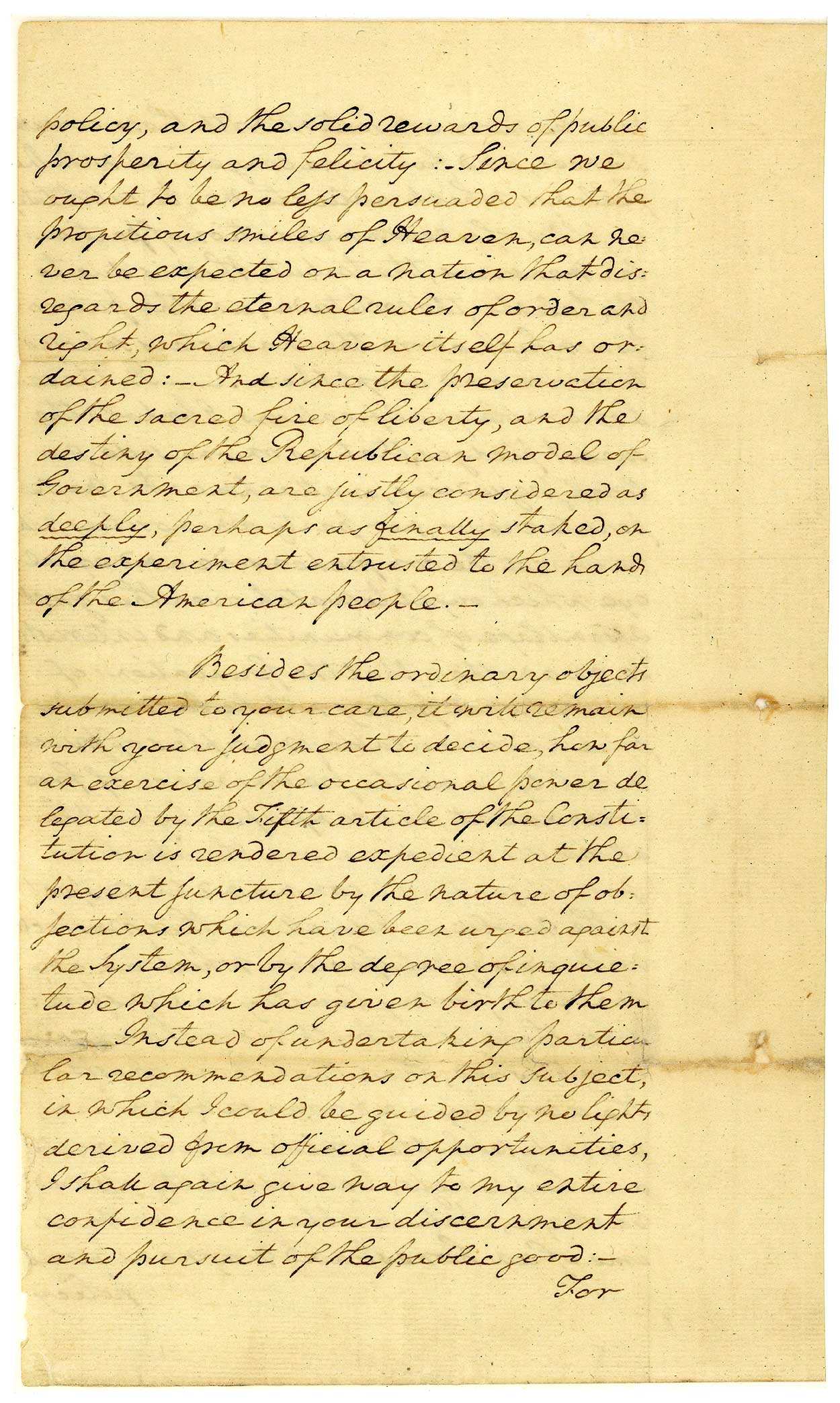

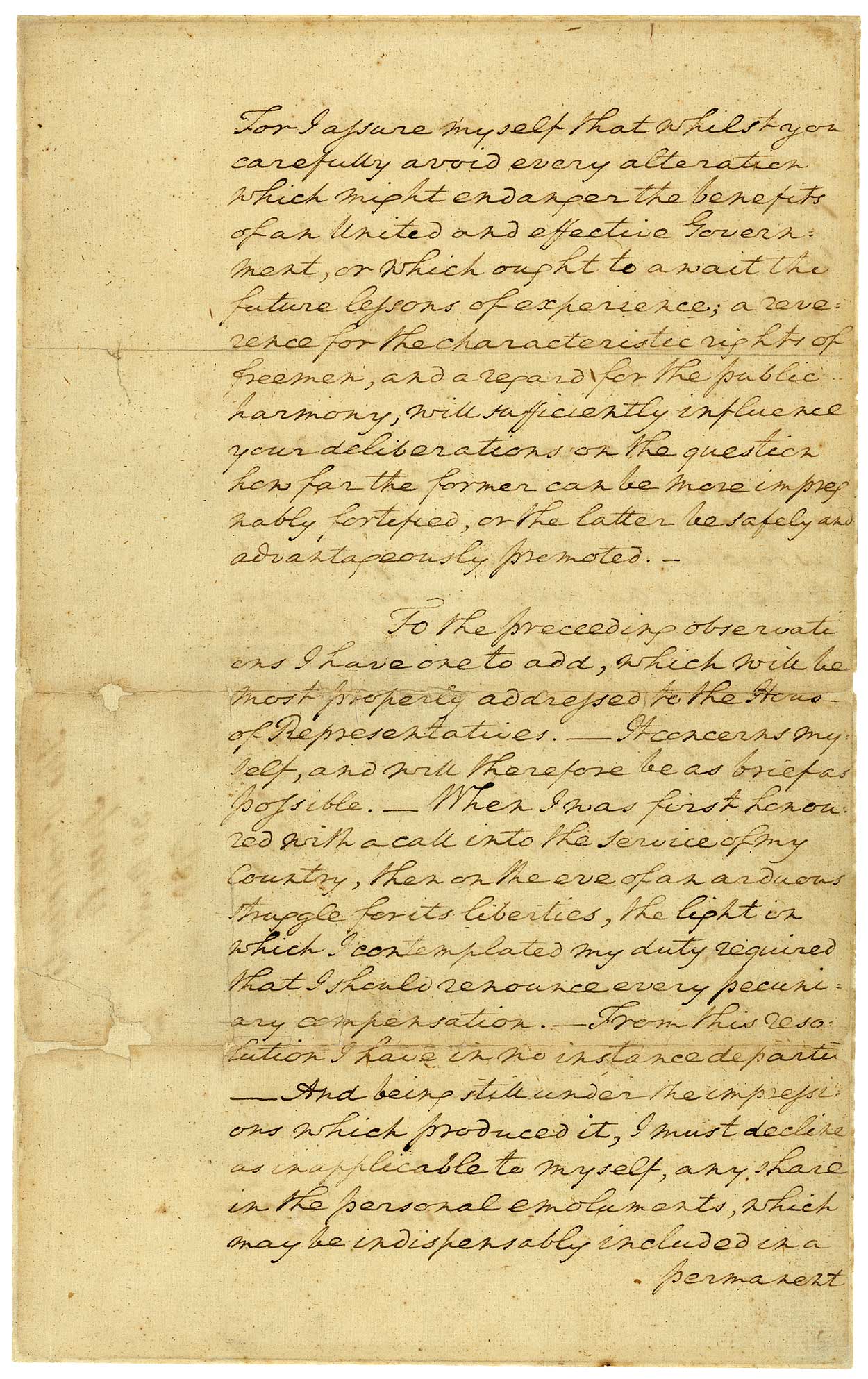

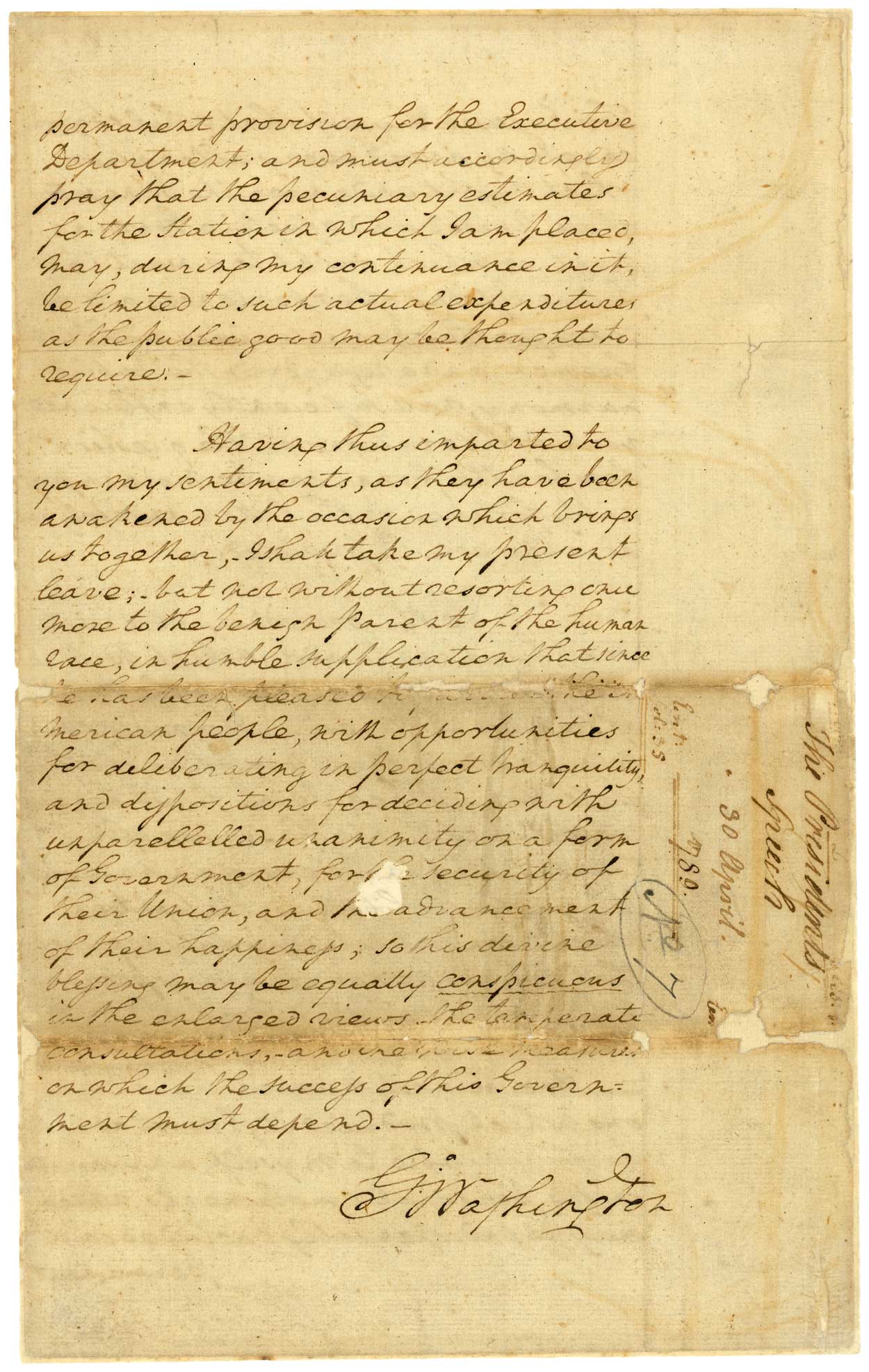

The Inaugural Address

President Washington did not audibly address the crowds, instead he humbly bowed his head in acknowledgment of the cheers, and before the fanfare and ovation ended he repaired to the Senate Chamber. His attendants and other dignitaries followed. Washington made his way to a specially prepared dais and took his seat. After Congress and the other dignitaries present were seated, the new President rose and delivered a short inaugural address.

The inaugural address in its entirety, transcribed from copies in the National Archives, can be found here.

Courtesy of the National Archives

St. Paul's Chapel

After Washington had delivered his inaugural address, he as well as the Senators, Representatives, New York State and City officials – as well as distinguished friends and guests, walked to St. Paul’s Chapel for a brief service.

Only three days prior to the inauguration, Congress had approved a resolution stating the following: “Resolved, That after the oath shall have been administered to the President, he, attended by the Vice-President and the members of the Senate and House of Representatives, shall proceed to St. Paul’s Chapel, to hear divine service to be performed by the chaplain of Congress already appointed.”

Congress had authorized two different chaplains, each of a different denomination. The Senate chose as their chaplain, the Reverend Samuel Provoost. He was an Episcopal Bishop of New York and the Rector of Trinity Church. The House of Representatives named the Reverend William Linn, a minister of the Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church as their Chaplain. Unfortunately for Re. Linn, the House did not act until May 1st, so he did not participate in the inauguration and it was left up to the Right Reverend Provost to perform the duty alone.

A “divine service” was indeed delivered by the Rev. Samuel Provost not preaching a sermon that day but rather he read from a Book of Common Prayer; a “proposed” rather than established version as the new American Protestant Episcopal Church had not yet adopted its prayers or order of service.

At the conclusion of the service, the President was escorted to his own house.

End to a Long Day

As the sun went down and the stars came up on the evening of April 30th, great bonfires were lit in the streets and eleven candles were put up in many of the houses. The front of Federal Hall was lit up with the great lights of these fires.

The President was driven from his residence in Franklin Square to that of Chancellor Robert Livingston in the lower part of Broadway. From the Chancellor’s windows, Washington was able to view the brilliant display of fireworks, under the direction of Colonel Bauman, as well as the full view of the cheering spectacle. It is said that the display of fireworks that evening to end the official program of that historic day was the finest this country had ever yet seen. At ten o’clock the president departed for the Executive Mansion but was forced to proceed on foot as the crowded streets made it impossible for his carriage to pass.

The morning after the inauguration, Washington received many calls from people such as Vice–President Adams, Governor Clinton, John Jay, General Henry Knox, Ebenezer Hazard, Samuel Osgood, Arthur Lee, the French and Spanish ambassadors, “and a great many other persons of distinction.”

Click here to download the souvenir of the centennial anniversary of Washington’s inauguration April 30, 1789 as the first president of the United States the birth of the American republic papers by Mrs. Martha J. Lamb.